Foundations #2: The Birth of REST

How Roy Fielding’s 2000 dissertation reshaped the web by embracing its constraints.

This article is part of the “Foundations” series, exploring the roots of well-known technologies, patterns, and solutions that quietly revolutionized our industry.

Introduction

Recently, in one of my consulting projects, I had to integrate a CRM system with an outdated Magento platform that still relied on a SOAP integration. It reminded me how painful it used to be, 20+ years ago, when our only choices were heavy, rigid integration methods that required verbose XML, complicated schemas, and endless debugging sessions.

Thanks to Roy Fielding, that’s not our current reality.

In this article, I’m going to cover:

What were the options to create distributed applications and integrations in early 2000;

The main issues that Roy Fielding addressed through his doctoral dissertation;

What lessons we can take from the way he thought about it.

The Context Before REST

In the late 1990s, the World Wide Web had exploded in popularity, yet the underlying model of interaction was poorly understood. HTTP was already widespread, but primarily treated as a transport mechanism for documents. Meanwhile, distributed object technologies such as CORBA, DCOM, and RMI were attempting to dominate the conversation on how systems should communicate.

From a software architecture perspective, these technologies shared common ground: they all attempted to abstract distributed communication into object-oriented calls, hiding the network behind familiar programming models. CORBA allowed invoking methods on remote objects as if they were local. DCOM extended the Microsoft COM model across machines. RMI let Java applications call methods on objects located in other JVMs.

While elegant in theory, this approach assumed homogeneity, required complex middleware, and often resulted in complicated integrations. The network was abstracted away, but at the cost of interoperability, scalability, and simplicity.

SOAP, introduced in 1999, took a slightly different path by leveraging XML over HTTP. But despite its promise of platform independence, SOAP still carried the same mindset: remote calls wrapped in complex envelopes, schemas, and contracts. It treated HTTP as a tunnel rather than embracing its inherent semantics.

These approaches all shared one thing: they were built with the mindset of making the network invisible. But the web was proving that exposing the network, and designing with its constraints in mind, was the key to global scale.

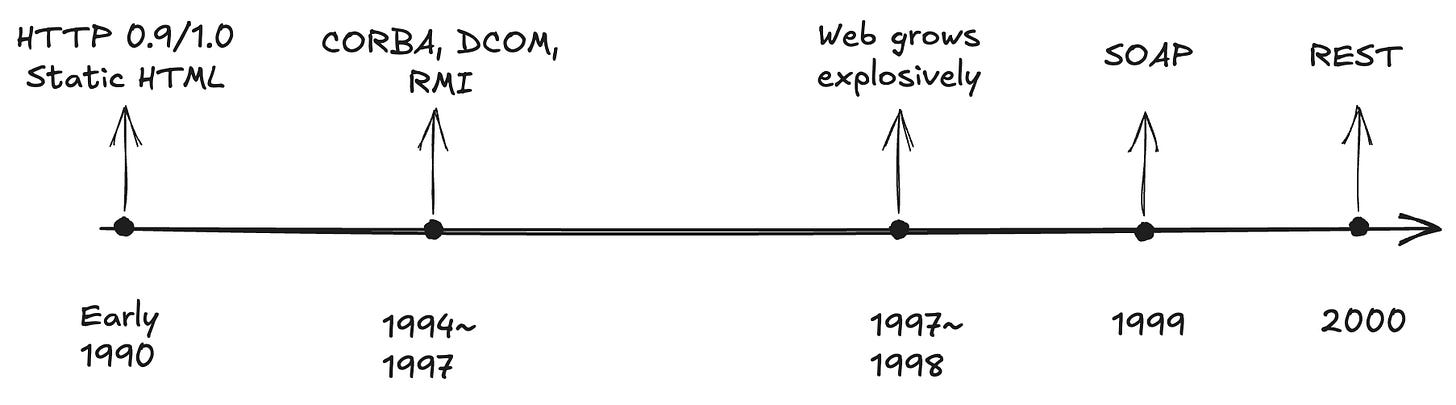

A Timeline of the Late 1990s

To better understand why REST emerged, it helps to place it against the chronology of distributed system technologies:

Early 1990s – The web takes shape with HTTP 0.9/1.0 and HTML, primarily serving static documents.

1994–1997 – Distributed object models rise: CORBA gains traction in enterprise systems, Microsoft pushes DCOM, and Java introduces RMI. The promise is transparency of remote method calls, but complexity and interoperability issues grow.

1997–1998 – The web grows explosively, challenging existing models of integration. Developers begin tunneling RPC-style calls over HTTP to bypass firewalls and proxies.

1999 – SOAP emerges, promoted by Microsoft and IBM as a standardized XML-based messaging protocol over HTTP. It simplifies some cross-platform concerns but adds layers of verbosity and rigidity.

2000 – Roy Fielding publishes his dissertation at UC Irvine, proposing REST as a distinct architectural style—leaning into the constraints of the web rather than hiding them.

This timeline shows the shift: from early web simplicity, to the complexity of distributed objects and SOAP, and then back to a simpler, constraint-based approach with REST.

What Roy Fielding Saw

Roy Fielding, deeply involved in the development of HTTP and the early web standards, noticed this mismatch. The web had succeeded not because it reinvented distributed computing, but because it relied on a few simple, robust principles:

URIs as a global addressing mechanism;

Stateless interactions that made each request independent;

Caching as a built-in efficiency layer;

A client–server separation that allowed independent evolution.

What the web lacked was a clear architectural model that explained why these choices worked and how they could be extended to future systems.

As Fielding put it:

“The World Wide Web has succeeded in large part because its software architecture has been designed to meet the needs of an Internet-scale distributed hypermedia system.” (Abstract)

His dissertation, published in 2000, was his attempt to codify the architecture of the web. Rather than following the object-oriented, RPC-based mindset of CORBA, DCOM, RMI, or SOAP, Fielding proposed a different path: embrace the web’s constraints instead of hiding them.

REST as a Historical Response

It’s important to see REST not just as a checklist of constraints, but as a historical response to the limitations of the time. Distributed object systems promised transparency, but they collapsed under the realities of latency, heterogeneity, and scale. SOAP attempted to patch this by standardizing messages, but it still carried complexity and rigidity.

REST, in contrast, was about working with the network as it is. By deliberately constraining design, it enabled:

Scalability through statelessness;

Evolvability through a uniform interface;

Interoperability through resources identified by URIs;

Resilience through layered intermediaries like proxies and caches.

The contrast was clear: while CORBA or SOAP required developers to agree on detailed contracts before integration, REST allowed systems to interact dynamically through standard operations and representations. Where the other options tried to hide the web, REST leaned into it.

Adoption of REST

REST’s adoption was gradual. In the early 2000s, most enterprises still relied heavily on SOAP, especially in large corporate and government integrations where WS-* standards promised reliability and security.

REST, meanwhile, spread organically through the open web. Companies like Amazon, eBay, and later Twitter and Facebook began exposing public APIs that leaned on REST principles. The simplicity of URIs and HTTP verbs made it accessible for web developers who were already fluent in these technologies.

By the late 2000s, REST had become the dominant style for web APIs, while SOAP retreated into more specialized enterprise use cases. This divergence highlighted a cultural as much as a technical shift: developers favored pragmatic, lightweight integrations over rigid, contract-driven systems.

Lessons Beyond REST

Looking at REST in this historical context, its greatest contribution was not just a new way of designing APIs, but a shift in mindset:

Constraints as enablers: by limiting design choices, REST created systems that could scale to Internet levels.

The web as the platform: instead of abstracting away the network, REST built directly on top of it.

Simplicity over complexity: REST thrived where object-distributed models struggled, because it embraced the reality of diversity and failure in the network.

More than two decades later, many of the technologies that once competed with REST have faded into history, while REST remains a baseline for how we think about integration.

Emerging Alternatives After REST

The dominance of REST eventually sparked new explorations. By the mid-2010s, developers were facing new challenges, like mobile clients with bandwidth constraints, applications requiring complex queries, and real-time updates that REST was not designed to handle elegantly.

This led to the emergence of GraphQL (2015), which prioritized flexible queries and minimized over-fetching; gRPC, which focused on performance and type safety through Protocol Buffers, and event-driven or streaming APIs using WebSockets and Kafka.

Each of these approaches can be seen as a response to specific limitations of REST, while still building on the lessons of constraint-driven architecture and interoperability.

Together, they show how REST provided a foundation, but not the final word in distributed system design.

Conclusion

Roy Fielding’s dissertation did not just propose an architectural style, it documented a turning point. It captured the lessons of the early web and set a direction away from the complexity of distributed objects and RPC toward a simpler, constraint-driven model.

As Fielding reminded us:

“A good architecture is not created in a vacuum. All design decisions at the architectural level should be made within the context of the functional, behavioral, and social requirements of the system being designed.” (Chapter 1)

The context of the late 1990s with SOAP, CORBA, DCOM, RMI, and the growing pains of the web, was exactly that environment. REST was his answer. And it remains a powerful reminder that the best architectures are those that embrace their constraints, not those that try to escape them.